…

…

CINQUE, SUNK AND SCOT FREE

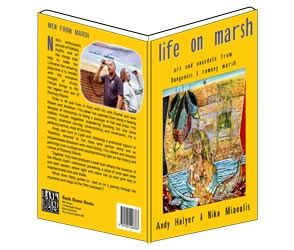

This is an excerpt from the book “Life On Marsh” Available for purchase at the bottom of this page

Dungeness and the surrounding area have seen massive changes in their topography in the last 1000 years. These changes contrast with most other areas in the UK which only morph slowly through millennia. The constant threat of the land being totally reshaped could be viewed as similar to living on the slopes of an active volcano.

Two thousand years ago the whole area of Romney Marsh was open sea, apart from a single long thin spit of shingle stretching from Rye to where Dungeness is now.

Two thousand years ago the whole area of Romney Marsh was open sea, apart from a single long thin spit of shingle stretching from Rye to where Dungeness is now.

At the time of the Roman invasion nearly two thousand years ago the sea level was still dropping as a consequence of the last ice age. The Romans quickly recognised the potential value of this fertile land, and started a drainage programme that continues to this day. Initially the Romans built large walls to drain the areas easily defended from the sea. After the Romans left in 400AD the locals, having fewer resources and less manpower, resorted to ‘inning’, which involved very small-scale draining and flood protection by individual families. This practice resulted in a patchwork system of tiny fields, some of which can still be seen today.

NANNY GOATS AND NAZIS

This is an excerpt from the book “Life On Marsh” Available for purchase at the bottom of this page

The isolation of Dungeness has not only encouraged and fostered but protected smuggling and other illegal activities over the years. The off the beaten track situation and somewhat mysterious reputation kept most people away and allowed a whole range of unusual practices and customs to develop, some of which persist to this day.

As with many isolated locations with difficult and dangerous access, Dungeness had and to some extent still has a very healthy barter economy. Most of the locals not only fished, but also kept goats for fresh milk, which roamed the shingle eating everything in their path – so much so that the area was locally known as Nanny Goat Island until recently. The area was also grazed by flocks of Lydd sheep within living memory. Both sets of ruminants helped to keep the shingle bare of all but the hardiest vegetation, allowing the area to evolve some of the unique flora and fauna it now boasts. Paradoxically, since the area has become more and more protected grasses have taken root. It is said that very soon they will have carpeted nearly all of the shingle, strangling out most of the unique plants and animals that are supposed to be protected.

As with many isolated locations with difficult and dangerous access, Dungeness had and to some extent still has a very healthy barter economy. Most of the locals not only fished, but also kept goats for fresh milk, which roamed the shingle eating everything in their path – so much so that the area was locally known as Nanny Goat Island until recently. The area was also grazed by flocks of Lydd sheep within living memory. Both sets of ruminants helped to keep the shingle bare of all but the hardiest vegetation, allowing the area to evolve some of the unique flora and fauna it now boasts. Paradoxically, since the area has become more and more protected grasses have taken root. It is said that very soon they will have carpeted nearly all of the shingle, strangling out most of the unique plants and animals that are supposed to be protected.

A PRETTY KETTLE OF FISH

This is an excerpt from the book “Life On Marsh” Available for purchase at the bottom of this page

Today it is common to observe rows of self-absorbed and anoraked anglers sitting like sentinels on shingle along the coast, wistfully wishing for a codling. These are the spiritual descendants of a once thriving fishing community that led a harsh existence here, clinging to these beaches in hope of a profitable catch.

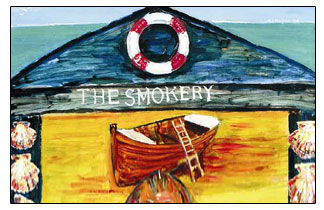

Herring fishing was the ‘gold standard’ of the local economy right back to the medieval period, when salted herring was traded from the Cinque Ports at the annual fair at Great Yarmouth. Remains of ‘herring hangs’ (towers for smoking fish) can still be seen in Lydd and Dungeness. With Jim Moate’s retirement this year we have unfortunately witnessed the last of this traditional fish smoking method on the Romney Marsh coast.

Herring fishing was the ‘gold standard’ of the local economy right back to the medieval period, when salted herring was traded from the Cinque Ports at the annual fair at Great Yarmouth. Remains of ‘herring hangs’ (towers for smoking fish) can still be seen in Lydd and Dungeness. With Jim Moate’s retirement this year we have unfortunately witnessed the last of this traditional fish smoking method on the Romney Marsh coast.

Along the coast are dotted net boiling ketches. These look like large laundry ovens, complete with chimneys and copper bowls, used to infuse nets with a tar solution to protect against the salt water.

In its heyday the fishing industry of Dungeness was serviced by a standard gauge railway service to Billingsgate. Remains of this railway, the narrow gauge railways from the beach to the road and railheads can still be seen today.

THE LIFEBOAT AND LADY LAUNCHERS

This is an excerpt from the book “Life On Marsh” Available for purchase at the bottom of this page

The Dungeness lifeboat has a long and distinguished history, being on one of the busiest shipping routes in the world until the advent of shipping lanes and modern navigational methods. It was one of the most used lifeboats in  Britain. Most lifeboats in Britain have a slipway that allows them to be launched at any stage of the tide. The constantly shifting shingle at Dungeness does not allow this so, like the fishing fleet, the lifeboat had to be launched by being pulled over lengths of hard wood placed at intervals on the shingle. These ‘woods’, as they are known, are 8 foot lengths of oak or ash, with ropes attached so they can be pulled out after the boat has passed over them and be quickly run round to the front of the boat to be reused in its journey to or back from the sea.

Britain. Most lifeboats in Britain have a slipway that allows them to be launched at any stage of the tide. The constantly shifting shingle at Dungeness does not allow this so, like the fishing fleet, the lifeboat had to be launched by being pulled over lengths of hard wood placed at intervals on the shingle. These ‘woods’, as they are known, are 8 foot lengths of oak or ash, with ropes attached so they can be pulled out after the boat has passed over them and be quickly run round to the front of the boat to be reused in its journey to or back from the sea.

This method of launching is still used by the local fishing boats today. In addition to this laborious task the lifeboat had to be pulled from and back into its shelter. The local tradition of women being responsible for the backbreaking and dangerous task of launching the lifeboat and the fishing boats is not, as it may seem, a misogynistic one. They traditionally did this job in order to make sure that the men stayed dry; to get wet before going out in an exposed boat in winter was hazardous in the extreme, and could even result in death. For that reason, not only were the boats launched by women but in rough seas women would carry their men to the boats to prevent them from getting wet. Women launched and retrieved the lifeboat until surplus American tractors found their way to the Marsh in the 1950s. The lifeboat is now launched and retrieved by a custom-built tracked vehicle.

OWLERS, SCARECROWS AND WITCHES IN EGGSHELLS

This is an excerpt from the book “Life On Marsh” Available for purchase at the bottom of this page

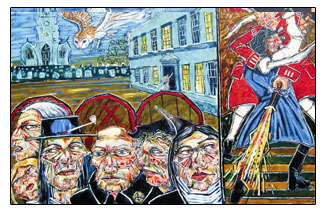

Dungeness and Romney Marsh have a long tradition of mystery, hauntings and supernatural goings on. To a large extent the area was a no-go area for much of the last couple of thousand years. Although the area was largely inaccessible because of its geography and topography, not to mention its reputation for being a very unhealthy environment (the Marsh was the last place where malaria was endemic in Britain and it was only eradicated in the early twentieth century), a large part of its unwelcoming reputation was deliberately cultivated by the local population, including its upper classes. It would have been virtually impossible for a high volume of contraband to be processed through the area without the involvement or compliance of nearly everybody resident there. This deliberate isolation was essential for the wide range of illicit goings on, which needed to be carried out in secrecy so there was as little risk as possible (even the penalty for wool smuggling was death).The area was considered so ungovernable by the Crown that it boasted its own currency and parliament until well into the nineteenth century.

Dungeness and Romney Marsh have a long tradition of mystery, hauntings and supernatural goings on. To a large extent the area was a no-go area for much of the last couple of thousand years. Although the area was largely inaccessible because of its geography and topography, not to mention its reputation for being a very unhealthy environment (the Marsh was the last place where malaria was endemic in Britain and it was only eradicated in the early twentieth century), a large part of its unwelcoming reputation was deliberately cultivated by the local population, including its upper classes. It would have been virtually impossible for a high volume of contraband to be processed through the area without the involvement or compliance of nearly everybody resident there. This deliberate isolation was essential for the wide range of illicit goings on, which needed to be carried out in secrecy so there was as little risk as possible (even the penalty for wool smuggling was death).The area was considered so ungovernable by the Crown that it boasted its own currency and parliament until well into the nineteenth century.

THE DUNGENESS LIGHTHOUSES

This is an excerpt from the book “Life On Marsh” Available for purchase at the bottom of this page

Dungeness lies at the southernmost point of Kent; it is an enormous flat  triangle of sand and shingle, possibly the largest area of its type in the world. Because of its flatness and, until recently, lack of habitation, coupled with its many sandbanks, unpredictable currents and sudden changes in weather, the whole area has seen thousands of shipwrecks over the years with countless lives lost. The presence of a light at the end of the peninsula has been an important navigational aid. Before any official lighthouse was built it is highly likely that the locals were paid to maintain a light (large bonfire) in order to warn shipping of the position of this highly dangerous hazard. As was the norm in those days, when times were hard (which they very often were), locals either ‘forgot’ to burn the warning fire or lit it somewhere else, giving a false impression of where the danger actually was. This practice became known as wrecking, for obvious reasons. The locals were then faced with a dilemma. They could either rescue the crew and passengers, hoping for a reward, together with any pickings that might be washed ashore, or – more often than not – they could murder any survivors and take everything.

triangle of sand and shingle, possibly the largest area of its type in the world. Because of its flatness and, until recently, lack of habitation, coupled with its many sandbanks, unpredictable currents and sudden changes in weather, the whole area has seen thousands of shipwrecks over the years with countless lives lost. The presence of a light at the end of the peninsula has been an important navigational aid. Before any official lighthouse was built it is highly likely that the locals were paid to maintain a light (large bonfire) in order to warn shipping of the position of this highly dangerous hazard. As was the norm in those days, when times were hard (which they very often were), locals either ‘forgot’ to burn the warning fire or lit it somewhere else, giving a false impression of where the danger actually was. This practice became known as wrecking, for obvious reasons. The locals were then faced with a dilemma. They could either rescue the crew and passengers, hoping for a reward, together with any pickings that might be washed ashore, or – more often than not – they could murder any survivors and take everything.

FOREWORD BY SIR DONALD SINDEN

I had been a neighbour in Chelsea of actor and author Russell Thorndike, who told me of the magic of Dymchurch and the Marsh so, at his instigation, in 1954, I bought the house in which I still live.

Later, in 1960, Russell played the pirate Smee to my Captain Hook in Peter Pan at the Scala Theatre in London. It was then that he presented duly inscribed copies of his Dr Syn books to my son Marc, but it was back in 1954 that I visited Dungeness for the first time and immediately fell under its spell – and I use the word ‘spell’ advisedly – perhaps ‘mesmerism’ could be even better. Of course this was before the power station defined its limits and ruined the scale.

Thank goodness The Pilot is still there, with Niko at the helm, its signpost showing the direction to ‘the other Land’s End’ and, blessing upon blessing, no terrible muzak!

Niko Miaoulis and Andy Holyer, sharing their combined knowledge, have produced an enchanting book on this fascinating promontory.

My thanks and best wishes to them both.

Sir Donald Sinden, CBE

|

UK – £5.99 + £2 Delivery |

WORLDWIDE – £5.99 + £4 Delivery |